Dr Katherine Trebeck– SA visit report excerpt

In September 2023, Dr Katherine Trebeck, political economist and leading global expert on the economics of wellbeing, presented to several groups from government and industry, offering valuable insights into how an economics of wellbeing can help support delivery of multiple policy goals for governments, and how it can enable business to meet its environmental and social objectives and be a business of choice for both customers and employees.

The wellbeing economy agenda is about constructing the economy so it delivers human and ecological wellbeing, rather than generating harm that necessitates ameliorative and corrective action (‘failure demand’).

Its core tenets encompass:

- Harnessing policy instruments, regulations, taxes, subsidies, business models, and so on to configure the economy so its outcomes meet the needs of people and planet.

- Appreciation of – and acting in accordance with – the economy as a sub-set of society and of nature, and therefore designing it to serve social and environmental goals (rather being an objective in its own right).

- Being nuanced about economic growth: asking what more is needed (and where and for whom) because it is aligned with what people and planet need, and what economic activities need to be powered down because they are misaligned with the needs of people and planet?

A wellbeing economy approach thus means asking:

- How does South Australia’s labour market support the wellbeing of people living and working in South Australia? What is the quality of jobs on offer, do they offer meaning and purpose, and who can access them? Is income sufficient to live on? How can more earnings equality, and work-life balance be attained?

- How does South Australia’s tax system support wellbeing, of people living and working in South Australia, and those beyond its borders? To what extent does the tax base and tax incidence encourage behaviours aligned to wellbeing, and discourage those counter to it (such as rent seeking)? How does the way taxes are levied reduce economic inequality? Does the level of taxation allow for sufficient government resources to support collective institutions and shared services that enhance wellbeing?

- How do businesses in South Australia (and those owned by South Australians) support the wellbeing of people living and working in South Australia, and of those beyond its borders? What sort of activities, goals, and enterprise models need to be encouraged, via regulation, tax breaks, and other means?

- How does decision-making support the wellbeing, of people living and working in South Australia, and beyond its borders? How are decisions taken, by whom, and how responsive are institutions to people’s needs? Are there opportunities for people to influence decisions that impact them? How diverse are the people elected to political office and working in South Australia’s public service?

- How does the way people treat each other support the wellbeing of people living and working in South Australia, and those beyond its borders? How can stigma and prejudice, racism and sexism be addressed? These are the historical roots of current inequalities, and they need to be addressed, recognising that the overlaps across them mean their cumulative impact is harsher than the sum of the parts.

- How do all these decisions impinge on the environment, in South Australia, and beyond its borders? How do South Australia’s production and consumption patterns, its emissions and use of ecosystems, impact the health of the planet and the environment here and overseas? Do they align with an understanding that decisions cannot be taken as if the economy is separate from the natural world and with the reality of finite planetary boundaries?

Governance for a wellbeing economy

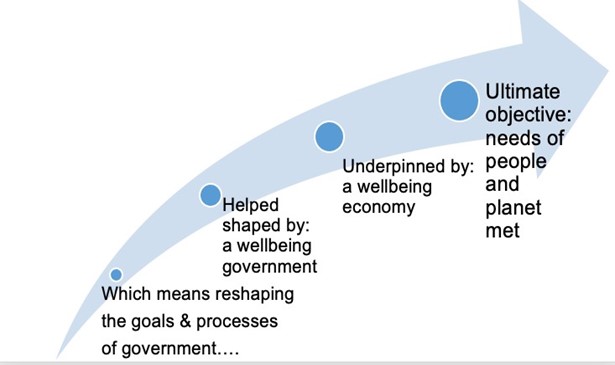

A wellbeing economy requires that government incorporates wellbeing goals across the policy cycle, and harnesses policy instruments to shape the economy accordingly. As shown in Figure 1, wellbeing in government is a necessary component of the wellbeing economy project, but not the same as it – it is part of attaining it, not a substitute for it.

Figure 1: The sequence of the wellbeing economy agenda

Figure 1: The sequence of the wellbeing economy agenda

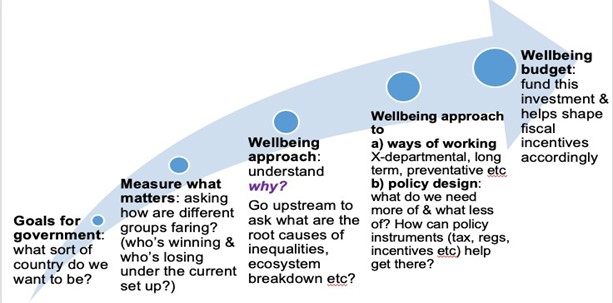

As shown in Figure 2, bringing wellbeing into government itself has an important sequence: understanding what matters; then measuring what matters; then making those measures matter via ways of working and policy design that looks holistically and upstream; then budgeting to direct resources and fiscal measures in ways that encourage the various pieces of the wellbeing economy jigsaw.

Figure 2: The sequence of wellbeing into government

Analysis of efforts by governments around the world to incorporate wellbeing goals and approaches into governance processes and economic policy making has found the following factors are important:

- A high-level mission or vision, underpinned by wellbeing measures and metrics. This brings into the frame various aspects of people’s lived experience that matter to their wellbeing and are often downplayed in traditional analyses. It would also show the importance of how wellbeing outcomes are distributed between individuals or groups (beyond simply considering the distribution of income or aggregate outcomes such as the economy writ large).

- Encompass environmental considerations to be truly multidimensional and so as not to compromise the wellbeing of people around the world and that of future generations (New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework, for example, is explicit about the resources needed to sustain wellbeing over time).

- Public involvement – especially for hitherto marginalised groups and those whose wellbeing needs particular attention – in developing this framework matters in and of itself (since wellbeing is about agency); but also for the legitimacy and mandate of the framework (including garnering cross-party support).

- Mapping, disaggregating, and regularly reporting against a dashboard of wellbeing goals and indicators offers a picture of the extent to which the government’s policy efforts (and associated budgets) are leading to enhanced wellbeing and can then be used to inform policy responses that attend to inadequate outcomes.

- Ministerial responsibility and accountability for both reporting and outcomes helps build in rather than bolt on the agenda and brings relevant agencies’ efforts to delivery of wellbeing outcomes. Parliamentary oversight is important and government auditors can help by offering quality assurance and independent auditing, with many countries extending this role to performance auditing.

- Legislation ‘hard wires’ the vision, reporting schedule, delivery mechanisms and plans for reviews and updates into government processes, (and means they are more likely to remain in place despite a change of government).

- Sustained championship is critical in driving attention, take-up and understanding of the importance of the agenda, and maintaining commitment. This is more sustainable if via strong agency structures or dedicated portfolios. An independent (and politically neutral) and sufficiently resourced watchdog/ commissioner function can ensure regular reporting, undertake additional research, hold governments to account and maintain relationships with key stakeholders, including the media.

- Officials across government will be better placed to deliver if they have support, guidelines, tools and training, including to adopt new ways of working, to use new analytical processes and to align their activities with the wellbeing goals.

- Cross-departmental work is essential – wellbeing issues do not align neatly with government silos nor pertain to a single sector. For example, New Zealand’s work to address mental health and addiction problems is not confined to its health system, but also involves justice and education stakeholders. Systems and cultures to enable this is crucial: for example, New Zealand changed its State Sector Act to enable more collaborative working within its civil service, while in the case of gender budgeting, half of the OECD countries that have implemented it have a dedicated interagency working group.

- Finally, this work is difficult and will take time. Building on what is already going well will make the changes easier.

Policy making for a wellbeing economy

No country around the world could be described as a wellbeing economy. Governments have, to varying degrees, experimented with different approaches and put in place various policy instruments that support wellbeing economy goals. Often, however, these are counteracted by other goals and undermined by countervailing forces. The latter South Australia may not be able to control, but there is scope for it to show leadership on the former – not just in Australia, but globally – in developing a coherent policy programme in accordance with an overarching wellbeing vision. No single change or policy is sufficient on its own, but together a suite of shifts can transform the economy’s purpose, design, and delivery. The changes can be understood as a jigsaw with multiple pieces. To help navigate the jigsaw, the practices of a wellbeing economy can be loosely clustered into four corners, the ‘4Ps’ of the wellbeing economy:

- Purpose

- Prevention

- Predistribution

- People powered

It is worth noting that the majority of policy instruments that need to be developed and rolled out are unlikely to be referred to as ‘wellbeing policies’ (or similar) and that most relevant practices are unlikely to be badged as being about ‘wellbeing’. Instead, their contribution to a wellbeing economy can be judged by the extent to which they are part of building an economy explicitly in line with the collective wellbeing of people and planet.

Corner | Description | Types of activities | Examples |

Purpose | The goal of the economy and the entities that comprise it deliver the needs of all people (including those beyond our borders) and planet (and all species on it). Not merely pursuing ‘growth’ in an abstract sense, but asking growth of what is needed, where, and for whom? Also important are valuing what matters – be it nature or community building or care in the home – rather than equating market price with true value. | Wellbeing frameworks and dashboards that shape government goals and policy, wellbeing (and outcomes) budgets, and pro-social businesses. At the micro level, businesses that seek to harness commercial viability in order to deliver social or environmental impact, especially evident in enterprises adopting business models more conducive to this (such as B Corps, social enterprises, community interest companies, cooperatives, Economy for the Common Good, International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN) practices, Conscious Capitalism, and so on). |

|

Prevention | Asking why a problem emerged to understand upstream drivers and plan and implement actions that tackle root causes. Designing an economy that gets things right first time around, rather than patching up symptoms downstream, once damage is incurred. | Circular economy activities (that reduce the need for beach clean ups); renewable energy (that lessen the need for carbon capture sequestration and storage); jobs that enable people to earn enough to live on (and reduce the need for food banks, rest assistance, and tax credits to top up wages); employment that encompasses autonomy, relatedness and competence, thus meeting people’s fundamental human needs (and thus reduce demand for anxiety treatments). |

|

Pre-distribution | Getting the economy to do more of the ‘heavy lifting’ in delivering sought outcomes by designing markets in a way that generates a more balanced distribution of economic resources in the first place, meaning less government intervention is necessary to redistribute and moderate the gap between rich and poor or attend to misallocation of resources, after the fact. | Mechanisms of predistribution include community wealth building (that builds economies from the local up via local ownership, local procurement, and local employment); worker cooperatives (where labour owns capital and the purpose of the business is to meet the needs of its members); and true cost accounting (that ensures environmental costs are incorporated and social impacts accounted for, giving a more accurate price signal to consumers). Living wages and pay ratios, and efforts to share work better can also help deliver better distribution without relying on government taxes and transfers. |

|

People powered | Putting a diversity of people at the forefront of shaping economic systems, rather than an economy designed by and for a narrow group. Who is at the table when budgets are designed or when economic strategies are written? When policies are prioritised? When business plans are shaped and investments weighed up? | Citizens assemblies help position dialogue amongst everyday people at the heart of government decision making. Participatory budgeting: where public money is deployed according to what local people decide it should be spent on. Public ownership of key service providers (perhaps water or energy providers or rail companies) and more employee input to decision making at the firm level (via, for example, employee representation on boards and employee ownership of firms themselves) will also help bring about economic democracy. |

|

The 4Ps in South Australia

South Australia has been a world leader in the energy transition and in the circular economy. It could be a leader in economic transformation. Across the 4Ps the sorts of approaches and activities this could entail include (with examples of their alignment with the South Australian Economic Strategy):

Purpose

- South Australia is in a good position in that the economic purpose conversation is being led at government level by the Department of Premier & Cabinet. The Economic Statement captures a purpose (‘An economy fit for the future, improving the wellbeing of all South Australians’) and has defined themes. These now need to be measured and mapped, and the results and goals used to guide all government decisions. This requires setting out ways of working, sharing case studies, and delivering training and cultural change programs within government to embed (and challenge business as usual thinking) and drive innovation in implementation. This means applying a holistic and upstream wellbeing lens to all government decisions.

- Explicitly and consistently recognise the extent and impact of the environmental crisis on South Australian’s health, livelihoods, and South Australia’s ecosystems. Acknowledge and undertake necessary change management in the operations of sectors and economic activities such as energy production and use, food and fibre, tourism, and manufacturing processes. No policy should be taken without consideration of what is compatible with 1.5 degrees limits on global warming.

- Develop a suite of ‘cornerstone indicators’ to galvanise public engagement in measuring what matters.

Economic Statement: ‘…where we care as much about the state our children and their children will inherit, as the headline statistics of today…A sustainable economy respects our natural resources and supports greater biodiversity, underpinning a better quality of life for all South Australians…We are often reminded of the need to live within planetary boundaries’.

Prevention

- Undertake analysis of the extent to which the State’s budget is deployed on ‘failure demand spending’ (spending that is reacting to negative outcome and seeking to ameliorate, repair, and fix after the fact). Use root cause analysis and similar techniques to understand the elements of the prevailing economic system that are responsible for the negative outcomes.

- Convene cross-departmental (and multistakeholder) working groups to generate holistic/ upstream solutions to challenges. This will likely necessitate new accounting rules and budgeting processes that take account of ripple effects and long-term costs and benefits.

- Make public facilities (such as schools) available for community activities and circular economy enterprises to make more efficient use of public infrastructure and bring citizens together in spaces of innovation and community building.

Economic Statement: ‘The Green Industrial Transition Roadmap…will provide the blueprint for how significant investment in renewable energy projects will drive our industries to plan, build and operate in a low emissions environment…Healthy ecosystems and greater biodiversity are…essential to South Australia’s quality of life and economic prosperity. Our social and cultural identity are underpinned by our healthy native ecosystems and diverse natural landscapes… The state’s early adoption of circular economy principles can also provide a path to prosperity through greater efficiency and sustainability’

Pre-distribution

- Use planning and procurement tools, taxes, and business advice services to bolster the proportion of pro-social businesses in the economy (and set a target to pursue). Wellbeing and economic statements should be explicit about the role of such enterprises in creating ‘An economy fit for the future, improving the wellbeing of all South Australians’.

- Enact a Community Wealth Building Act that aligns procurement and planning decisions

- Use state tools to tax wealth and unearned income (such as a ground rent where the state retains ownership of land)

- Use state levers to support the growth of diverse models of housing provision (such as cooperative housing and community land trusts)

Economic Statement alignment: ‘The South Australian Government is a significant purchaser and employer in the economy. It can meaningfully shape outcomes through its procurement policies, with $8.5 billion in goods and services purchased each year. Government can shape and even co-create markets through associating key outcomes with procurement—whether that be local content or sustainability metrics. We can also drive innovation through our procurement activities, leveraging government purchasing power to develop new products or methods of production’. And ‘When more South Australians are in meaningful and skilled work, and are paid fairly for their contribution. When all South Australians feel the benefits of our strong economy, we’ll know we got it right’.

People powered

- Undertake a mixed methods and inclusive community conversation process to develop a high-level vision for the state

- Convene citizens assemblies to build a mandate for aspects of economic transition

- Ring-fence a portion of local and state government budgets to be deployed via Participatory Budgeting.

Economic Statement: ‘Our ambition is to increase all South Australians’ participation in our economy and society, supporting communities and individuals to thrive. In addition to personal characteristics such as age and gender, place-based circumstances impact our ability to work, study and play—leading to the disparities in outcomes across regions and communities we see today. Reducing barriers to participation is at the core of our vision to build a more inclusive economy… at the heart of our economy is the South Australian people’.

Learning for a wellbeing economy

Building a wellbeing economy is not an easy task. It requires commitment and willingness to work through resistance. Fortunately, South Australia is not alone on this journey and can learn from the experiences and common challenges of other governments charting a similar path. As appropriate, state government actors should join:

- The Wellbeing Economy Governments partnership (WEGo)

- The Wellbeing Economy Alliance policy makers network

- The Centre for Policy Development’s wellbeing government round tables

The South Australian Government could lend support for creation and development of a network of enterprises, scholars, community builders, and thought leaders who drive and demonstrate the wellbeing economy in practice. This could form part of the emerging Australian hub of the global Wellbeing Economy Alliance movement and would help connect the actors working in different sectors and spheres of influence and showcase the work of pioneers that demonstrate that change is not just desirable, but feasible.